How to Classify and Vet AI Tools in Education (2026)

%20resized.webp)

Introduction: Why is AI risk assessment a priority?

Higher education doesn’t need another abstract reminder that “AI is here.” In 2026, the pressing reality is operational: institutions are already using AI, often across teaching, support, and administration, while policy, procurement, and risk practices lag behind. That gap creates the conditions for the outcomes university leaders want to avoid: inconsistent oversight, unclear accountability, budget surprises, and compliance exposure.

Recent sector research shows how widespread adoption is—and how uneven readiness remains. A UNESCO global survey of higher education institutions found that 19% report having a formal AI policy, while 42% say AI guiding frameworks are under development, a sign that many institutions are still catching up on governance while use accelerates. At the same time, EDUCAUSE commentary on institutional practice notes that less than 40% of surveyed institutions have AI acceptable use policies, meaning a majority may still be operating without a shared baseline for “what’s allowed, by whom, and under what controls.”

It’s not just legal teams raising flags. When institutions hesitate on AI deployment, the barriers often map directly to risk and cost. In WCET’s 2025 survey of institutional practices and policies, among respondents whose institutions were not using AI in governance, top reasons included data security concerns (36%), ethics/bias concerns (31%), and costs to the institution (31%). This is a useful truth for senior leaders: compliance and budget discipline are connected, because uncertainty drives delays, duplicative reviews, and tool sprawl.

Meanwhile, higher-ed technology leaders are increasingly aware that AI isn’t “free” even when the demo looks simple. EDUCAUSE survey findings reported that only 22% of respondents said their schools had implemented institution-wide AI strategies, 55% said AI strategy was rolling out ad-hoc, and 34% believed executive leaders were underestimating the cost of AI. Put plainly: AI risk assessment has become a leadership issue because unstructured adoption is expensive - in time, procurement cycles, and downstream compliance work.

This guide aims to make AI risk assessment approachable for the people who carry the accountability: CIOs, IT directors, procurement leads, legal counsel, DPOs, and academic leaders tasked with safe adoption. It is not legal advice, but a practical way to align around three questions:

- What risk class is this tool likely to fall into (and why)?

- What should we ask vendors to prove, before we sign or scale?

- How do we avoid hidden implementation costs that show up after the pilot?

We’ll anchor the discussion in the EU AI Act’s risk-based logic, because its framework is influencing vendor posture globally, and then translate it into procurement-ready, systemized action plans.

Chapter 1: What are the AI Risk Classifications in Higher Education?

Note: This chapter is informational and designed to support institutional planning. It is not legal advice.

Higher education leaders are being asked to “adopt AI,” but the more urgent question in 2026 planning cycles is: which AI uses are safe to deploy quickly, and which require formal risk controls (or should be avoided entirely)?

That’s exactly what the EU AI Act is designed to clarify through a risk-based approach with different obligations depending on how an AI system is used. The Act applies broadly to providers and deployers in the EU, and it can also apply to organizations outside the EU when the system’s output is used in the European Union.

Just as importantly for education: the AI Act explicitly calls out education and vocational training as a domain where certain AI uses are treated as high-risk, because they can materially affect a person’s educational and professional trajectory.

1.1 What the EU AI Act changes for universities and colleges

There are three practical implications for higher ed teams (CIO, legal, procurement, data protection, and academic leadership):

- Risk classification becomes a procurement prerequisite.

If you cannot classify the tool’s use case, you can’t reliably determine what evidence you need (e.g., transparency notices, logging/auditability, human oversight, post-market monitoring). - Some uses are outright prohibited.

The European Commission’s risk pyramid lists “unacceptable risk” practices that are banned, including emotion recognition in educational institutions. - Timelines matter.

The AI Act’s general date of application is 2 August 2026, while prohibitions and some general provisions applied earlier (from 2 February 2025). Certain governance provisions and obligations for general-purpose AI models apply from 2 August 2025.

For institutions, this means 2026 readiness work is less about “Do we have an AI policy?” and more about:

Do we have a repeatable way to classify tools, document decisions, and enforce controls in the systems our campus actually uses?

1.2 The four AI Act risk levels, translated for higher education

The European Commission summarizes the Act as a four-level risk model: unacceptable, high, limited, and minimal/no risk.

Your internal classification work should use this same structure because it maps directly to institutional obligations and vendor due diligence.

Unacceptable risk (banned)

These are practices considered a clear threat to safety, livelihoods, and rights. The Commission lists prohibited practices, including emotion recognition in workplaces and education institutions.

Higher ed examples (illustrative):

- “Emotion detection” during exams or lectures to infer engagement, stress, deception, etc.

- AI systems that manipulate vulnerable groups (e.g., students in distress) in a way that meaningfully distorts behaviour.

Institutional action: treat these as non-starters in procurement and policy.

High-risk (allowed, but regulated)

High-risk systems are allowed if they meet specific requirements and controls—because the use case can significantly affect people’s rights and opportunities.

In higher education, the AI Act explicitly points to systems used in education that may determine access to education or influence professional life (e.g., scoring of exams).

Higher ed examples (illustrative):

- AI used to evaluate learning outcomes in a way that determines grades or progression.

- AI used for admissions decisions or assignments to programs.

- AI used to monitor or detect prohibited behaviour during tests.

We’ll unpack these in Section 1.3.

Limited risk (transparency risk)

These systems are typically permitted but require transparency, especially when humans are interacting with an AI system (e.g., chatbots). The LearnWise Product Classification documentation summarizes this as “AI systems that are interacting with humans,” including chatbots and generative AI that must be disclosed to users.

Higher education examples (illustrative):

- A student-facing support assistant answering policy or process questions.

- A course-aware study assistant that helps students navigate course materials (with proper transparency and safeguards).

Minimal or no risk

The European Commission notes that the Act does not introduce rules for AI deemed minimal or no risk, and gives examples like spam filters. The LearnWise documentation similarly describes minimal/no risk as common consumer-facing AI applications (e.g., spam filters, predictive text).

Higher ed examples (illustrative):

- Back-end IT tooling for spam filtering and generic system optimisation.

- Non-sensitive automation that doesn’t affect rights or academic decisions.

1.3 What makes an education AI tool “high-risk” under the EU AI Act?

This is where higher education leaders often need the clearest translation: high-risk is not “AI that feels scary.” Under the Act, high-risk is defined by use case.

In Annex III, the AI Act lists education and vocational training high-risk use cases, including AI systems intended to:

- Determine access/admission or assign individuals to educational institutions/programs

- Evaluate learning outcomes (including when used to steer the learning process)

- Assess the appropriate level of education an individual will receive or can access

- Monitor/detect prohibited behavior during tests

The Act’s recitals emphasize why: these uses may shape the educational and professional course of someone’s life and affect their ability to secure a livelihood.

A practical “high-risk” lens for campus teams

When you’re classifying an AI tool in education, ask:

- Is it deciding, scoring, or determining outcomes?

If the AI is effectively producing a result that a student’s future depends on (admission, placement, grading, progression), you are in high-risk territory. - Is it steering the learning process based on evaluated outcomes?

Even if it looks like “personalization,” if that personalization is driven by evaluated outcomes that materially influence a student’s trajectory, treat it seriously. - Is it connected to exam integrity monitoring?

Proctoring-adjacent tools often trigger higher scrutiny; certain approaches can also run into prohibited practices (e.g., emotion recognition).

1.4 The nuance: not everything used “in education” is automatically high-risk

This is one of the most helpful operational details in the Act, and it’s especially important for LMS-native copilots, tutoring, and feedback assistants.

Article 6 explains that while Annex III systems are generally high-risk, an Annex III system may not be considered high-risk if it does not pose a significant risk of harm, including by not materially influencing decision-making, and if it meets certain conditions, such as performing:

- A narrow procedural task

- An improvement to a previously completed human activity

- pattern detection without replacing a human assessment (without proper human review)

- A preparatory task to an assessment relevant to Annex III use cases

However, the Act also notes that an Annex III system is always high-risk when it performs profiling of natural persons.

Why this matters for universities

This “not automatically high-risk” nuance is what allows many institutions to deploy assistive AI in teaching and support, as long as:

- AI outputs are advisory, not final decisions

- Humans remain accountable and can review/override

- The system is not profiling students in ways that materially affect outcomes

- Transparency and logging are implemented as appropriate

This is also why implementation design (human-in-the-loop, role-based access, auditability, scoping of knowledge sources) is as important as the model itself.

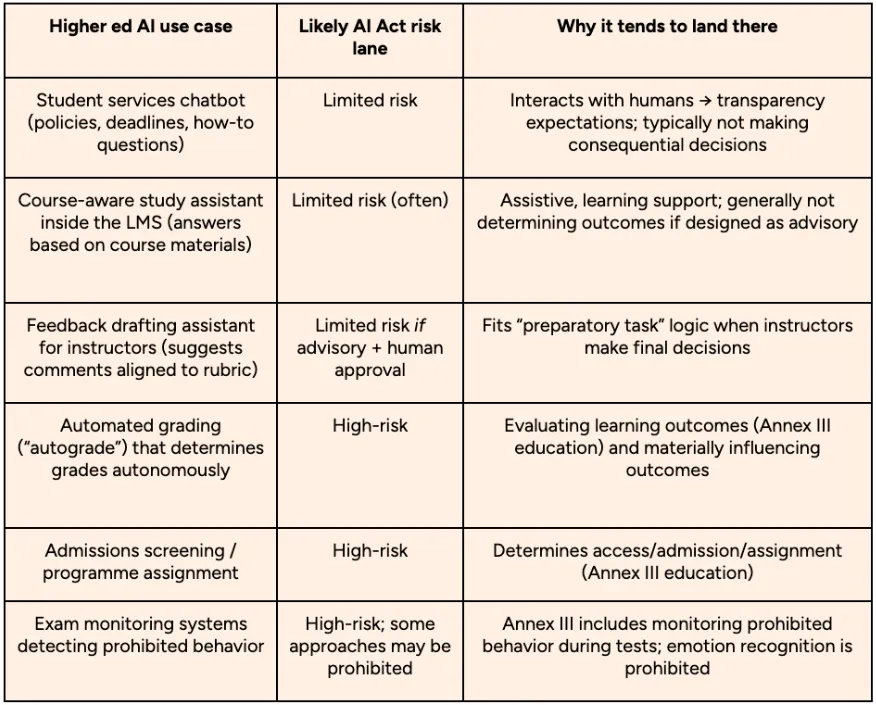

1.5 A cheat sheet: common higher education AI use cases and where they often land

Below is a simplified mapping to help teams orient quickly. (Final classification always depends on intended purpose, configuration, and local context.)

1.6 LearnWise’s product classification approach

In the LearnWise Product Classification Documentation, LearnWise explicitly classifies its products under the AI Act and explains the reasoning (including where risk shifts depending on configuration).

A few useful examples of how that documentation frames risk in education:

- AI Feedback & Grader: The documentation distinguishes between a non-autograde version (advisory, instructor approves) and an autograde-enabled version (more autonomous). It notes that when the tool is advisory and the instructor must review/approve, it may be treated as a preparatory task and therefore limited risk; while autograde can push it toward high-risk classification because it engages in decision-making around learning outcomes.

- AI Student Tutor: The documentation positions the tutor as limited risk when it supports learning with course materials without materially influencing decisions, and it emphasizes the distinction between “used in an Annex III sector” and “actually performing Annex III high-risk functions.”

- AI Campus Support: The documentation describes a support assistant that interacts with humans and escalates complex cases to a help desk, framing features as minimal/limited risk with transparency expectations, and discussing general-purpose AI system considerations.

The bigger takeaway for CIOs, legal, and procurement: risk classification should be written down, feature-specific, and configurable. If a vendor can’t articulate how a “mode” (e.g., autograde vs. draft-only) changes classification and obligations, you’ll likely inherit that ambiguity during procurement and governance.

1.7 What to do prior to vendor evaluation: evaluating your state of AI

If you want to make the vendor assessment and procurement processes less contentious in your organization, here are a few steps you can take before you begin:

- Create an “AI tool inventory”: Capture every AI system in use (pilot or production), who uses it, where it’s embedded (LMS, website, staff portal), and what decisions it touches.

- Classify each tool by intended use: Use Annex III education triggers as your first filter.

- Document “why” (and treat it as living): The AI Act anticipates evolving guidance and clarifications, including guidelines the Commission planned to provide on classification implementation. Your documentation should be reviewable, repeatable, and updateable as tools evolve.

Chapter 2: How to assess AI tools and Vendors in Higher Education for CIOs and Procurement Teams

Note: This chapter is practical guidance for institutional evaluation. It is not legal advice.

Once you understand how AI risk is classified (Chapter 1), the next challenge is operational: how do you evaluate AI vendors consistently across IT, legal, procurement, and academic stakeholders, without dragging the process out for months?

In 2026, the institutions that move fastest (and safest) are the ones with a repeatable evaluation approach - one that separates “nice demo” from “enterprise-ready,” and makes it easy to answer:

- What data is being accessed, stored, and processed?

- What controls exist (identity, roles, logs, approvals)?

- How transparent is the system about how it generates outputs?

- Can we prove compliance and govern usage over time?

- Is the cost model predictable enough to scale?

Our AI Tool Evaluation Framework was designed to make these vendor conversations more transparent and evidence-based, especially for institutions comparing multiple AI tools across tutoring, feedback, student support automation, and analytics.

Below is a procurement-friendly playbook you can use in RFPs, vendor calls, and pilots.

2.1 A simple 3-stage evaluation flow: before, during and after demo

One reason AI procurement gets stuck is that teams evaluate everything at once. Instead, run your evaluation in three clear phases.

Phase A: “Evidence first” (before the demo)

Ask vendors to provide the materials that will determine whether a pilot is even worth running.

The LearnWise framework recommends requesting, prior to demo if possible, institution-standard documentation such as:

- HECVAT completion (or equivalent security questionnaire response)

- Accessibility documentation, such as an ACR from a VPAT (or as much detail as possible if they can’t provide it yet)

- Data privacy and security documentation relevant to higher ed (e.g., SOC2 Type II, FERPA-aligned materials)

- A clear statement on ethics and governance (transparency, non-discrimination)

- Documentation explaining institution environment separation—how institutional data is separated and not used in the larger model

Why this matters: it prevents your team from investing time in a pilot before the vendor can meet baseline requirements.

Phase B: “Show, don’t tell” (during the demo)

During the demo, focus on the capabilities that matter most for institutional risk and operational fit. The framework calls out demo priorities like:

- Accuracy and reliability (how hallucinations are mitigated; how accurate institutional information is kept)

- Human handoff (how sensitive or complex issues are escalated to humans; what the workflow looks like end-to-end)

- Content management (can internal teams update knowledge and fine-tune responses using trusted institutional content?)

- Accessibility and availability (what does the interface look like for all learners?)

Phase C: “Prove you can operate at campus scale” (after the demo)

After the demo, require the details that determine whether the system can live safely inside your institutional ecosystem:

- Implementation plan (a clear, time-sensitive rollout plan)

- How system updates are handled when knowledge updates

- How students can flag an incorrect AI response and where it goes

- Integration support, including whether they support LTI 1.3, and how they connect to your LMS/SIS/CRM ecosystem

- Analytics and reporting examples tied to KPIs (engagement, accuracy, common questions, adoption patterns)

2.2 The evaluation dimensions that matter most

Many institutions evaluate AI as if it were a standard SaaS tool. The difference is that AI systems produce outputs that can influence student decisions, faculty workflows, and institutional trust. That means your evaluation has to test more than integration.

The AI Tool Evaluation Rubric provides a structured scoring lens across five major areas.

Here’s how to apply it in an approachable, procurement-friendly way:

1) Accessibility & inclusion (can everyone use it?)

The rubric highlights two things institutions often overlook until late:

- WCAG 2.1 AA compliance and screen-reader compatibility

- Non-English handling, including multilingual input/output and non-English data sourcing

For many institutions, accessibility and multilingual capability aren’t “nice-to-haves”; they’re requirements that directly affect adoption, equity, and legal exposure.

2) Technical reliability + LMS fit (does it actually work in your environment?)

The rubric emphasizes:

- LMS integration and setup without unusual extensions or workarounds

- Stability and reproducibility (consistent outputs under consistent conditions)

- Scalability to large user bases (10k+ without performance degradation)

This is where many AI pilots fail: the tool works in a demo, but becomes brittle when it hits real institutional complexity.

3) Content quality, citations, and data sourcing (can you trust what it says?)

The rubric is explicit: high-risk systems are not just “what the model is,” but whether outputs are reliable, grounded, and verifiable.

It scores:

- Accuracy and reliability (hallucination frequency)

- Source citation and attribution (verifiable sources, not vague “web search”)

- Data sources and coverage (quality and currency of underlying sources)

AI Tool Evaluation Framework.xl…

For compliance-focused stakeholders, citation and traceability are essential, especially in student support and academic contexts.

4) Ethical, legal, and financial framework

This section is the bridge between legal/compliance and procurement reality. It covers:

- FERPA/GDPR compliance expectations

- Intellectual property and data rights (especially whether student/institution data can be used for model training or monetization)

- Cost of use (transparent licensing vs unpredictable or “mandatory individual fees”)

This is where hidden risk becomes hidden cost. If your institution cannot predict usage costs or clarify data rights, scaling becomes a budget and governance problem, not just a technical one.

5) Pedagogical impact and fairness

The rubric encourages institutions to test:

- Bias mitigation

- Process transparency (how results are generated)

- Educator training resources

Even if your pillar page is compliance-led, this dimension matters because governance teams will ask: “What are the consequences of deployment in learning environments?”

2.3 What to ask vendors: the “CIO + legal + procurement” question set

Here’s a practical set of questions, aligned to the framework and rubric above, that you can use directly in vendor calls:

Data and privacy

- What institutional data does the system access (content, user roles, logs)?

- What is retained, for how long, and where is it stored?

- Can the vendor provide privacy/security documentation in advance of a pilot?

- Does the vendor guarantee that institution data is separated and not used in the broader model?

Governance and auditability

- Are prompts configurable and reviewable (by role or institution)?

- Is there a usable audit log of interactions and administrative changes?

- Can students/users flag incorrect responses and where does that go operationally?

Integration and identity

- Do you support LTI 1.3? How does that look in our LMS?

- Do you support SSO and RBAC (role-based access control)?

- What happens when the LMS content changes - do outputs update and how quickly?

Quality and trust

- How do you mitigate hallucinations and ensure accuracy during peak usage?

- Do you provide citations and verifiable attribution to sources?

Budget predictability

- Is pricing fixed or usage-based? If usage-based, what controls exist to prevent budget overruns?

- Are any essential features locked behind add-on pricing tiers?

2.4 Red flags to watch for

This is the shortlist that saves teams months of wasted procurement cycles:

- No accessibility documentation or clear WCAG alignment path

- Opaque output generation (no process transparency, no citations)

- Unclear data rights (vendor can reuse institution/student data for training)

- No environment separation explanation (institution data potentially mingled)

- Token/usage pricing with no guardrails (budget volatility)

- No demonstration of human handoff/escalation workflows

- Integration depends on workarounds (extensions, manual exports, brittle setup)

2.5 How to involve legal and data protection officers without slowing everything down

Many institutions make the mistake of involving legal too late (after the vendor has momentum and champions). Instead:

- Bring legal/DPO in at Phase A (“evidence first”), focused on documentation and data rights

- Use the rubric categories (privacy, IP, cost) to structure questions so legal can respond quickly

- Keep the pilot phase limited to what can be safely evaluated with scoped data and clear boundaries

- Document decisions in a consistent, re-usable format so every tool doesn’t become a brand-new review

This transforms legal from a “final gate” into a structured partner in risk management.

Download: AI Readiness & Risk Assessment Checklist

If you want to operationalize Chapter 2 immediately, use a single checklist that can follow you from RFP → demo → pilot → approval.

📥 Download: AI Readiness & Risk Assessment Checklist

Chapter 3: How to avoid hidden AI implementation costs in higher education?

AI procurement conversations often start with capability (“Can it tutor? Can it grade? Can it answer questions?”). But the institutions that scale AI responsibly in 2026 tend to start with a different question:

What will it cost for us to go from pilot to long-term implementation?

Hidden costs rarely come from a single line item. They show up as budget volatility, extended legal review cycles, integration rework, and the slow creep of “shadow AI” tools that bypass governance because the official route takes too long.

Sector research suggests this is not a fringe concern. EDUCAUSE survey reporting found that only 22% of respondents said their schools had implemented institution‑wide AI strategies, 55% said AI strategy was being rolled out ad‑hoc across pockets of the institution, and 34% believed executive leaders are underestimating the cost of AI. The same reporting noted that only 2% said there are new funding sources for AI projects.

In other words: many institutions are experimenting widely while paying from existing budgets, making cost discipline a governance requirement, not a “nice to have.”

3.1 The real cost problem: uncertainty

In WCET’s 2025 survey of institutional practices, when respondents explained why their institutions were not using AI in governance or operations, “costs to the institution” was among the top reasons, alongside data security and ethics/bias concerns. For governance, cost was cited by 31%; for operations, 30%; and for instruction and learning, 33%.

This is an important context for CIOs and procurement teams: the cost challenge isn’t only licensing. It’s the uncertainty and friction that follows unclear risk posture, especially when compliance teams, security teams, and academic leaders don’t have a shared evaluation model.

This is why the evaluation process should treat budget predictability as a first-class risk control. The own AI Tool Evaluation Rubric makes this explicit by scoring vendors on “Cost of Use” (transparent licensing vs. unpredictable or mandatory individual fees) and tying cost predictability to sustainability.

3.2 The three hidden-cost traps (and how to avoid each)

Trap 1: Token-based pricing and “usage surprise” budget volatility

Usage-based models can look attractive at pilot scale, until adoption grows, peak periods hit (start-of-term, finals), or a feature expands usage (e.g., tutoring + support + feedback).

Common ways this shows up:

- The pilot is funded centrally, but ongoing usage is pushed to departments.

- Costs spike during predictable academic cycles.

- Teams avoid expanding to more courses because finance can’t forecast the run rate.

How to avoid it:

- Ask vendors to provide a 12-month cost projection at multiple adoption levels (e.g., 10%, 30%, 60% of students), including seasonal peaks.

- Require pricing guardrails: hard caps or agreed ceilings.

- Prefer cost models that map cleanly to how higher ed budgets work (fixed annual license, fixed enrollment bands, or fixed modules).

- Document “who pays” before rollout - central, IT, faculties, or blended.

This aligns with the “Cost of Use” sustainability criteria in your rubric: predictable licensing and no hidden upcharges are a meaningful signal of enterprise readiness.

Trap 2: “We’ll classify it later” = legal review delays and rework

When teams don’t classify the AI use case early (limited vs high risk, transparency obligations, documentation requirements), legal and compliance reviews tend to expand midstream, often late in the process, after champions have already socialized the tool.

This creates real cost even if the vendor is “free” or low-cost:

- Staff time spent in repeated reviews

- Procurement delays that push deployment into the wrong academic window

- Pilot fatigue (“we tried AI and it took 9 months to approve”)

- Renewed spend on alternatives when timelines slip

This problem shows up in broader reporting too. Only 2% of institutions are supporting AI initiatives through new sources of funding, and pointed to ongoing hurdles with funding and policy development. When the funding isn’t new, every additional month of review is an opportunity cost: fewer projects delivered, less capacity, and more “tool sprawl” as departments seek workarounds.

How to avoid it:

- Make “risk classification” a required pre-step in procurement (even a lightweight first-pass).

- Require vendors to provide a standardized “evidence pack” before the pilot. Our AI Tool Evaluation Framework explicitly recommends collecting artifacts like HECVAT responses, accessibility documentation (ACR/VPAT), privacy/security documentation, ethics/governance approach, and environment separation, ideally in advance of the pilot.

- Create a single intake route so legal isn’t reviewing the same class of tool five different times across departments.

Trap 3: Shadow AI and tool sprawl (the hidden cost)

When the formal route is slow or unclear, AI adoption doesn’t stop, it fragments. Individual teams add tools for:

- Tutoring and study support

- Draft feedback and grading acceleration

- Student services chatbots

- Admissions communications

The cost isn’t only financial. It’s the compounding operational overhead:

- Multiple vendors, renewals, and contracts

- Repeated security and privacy reviews

- Inconsistent responses and user experience

- Scattered analytics that can’t show institutional ROI

- Uneven policy enforcement (and uneven compliance exposure)

WCET’s survey reinforces that barriers differ by domain: for governance, data security and ethics/bias were the top concerns; for operations, cost and shifting leadership priorities were significant barriers. That pattern matches what many institutions experience: governance uncertainty creates shadow usage; then operational cost and complexity follow.

How to avoid it:

- Maintain a live “AI tool register” (what tools exist, who owns them, what data they touch).

- Approve a small set of vetted tools and publish them (reduces the incentive to go rogue).

- Use one evaluation checklist across procurement, legal, and IT, so departments know what the “yes path” looks like.

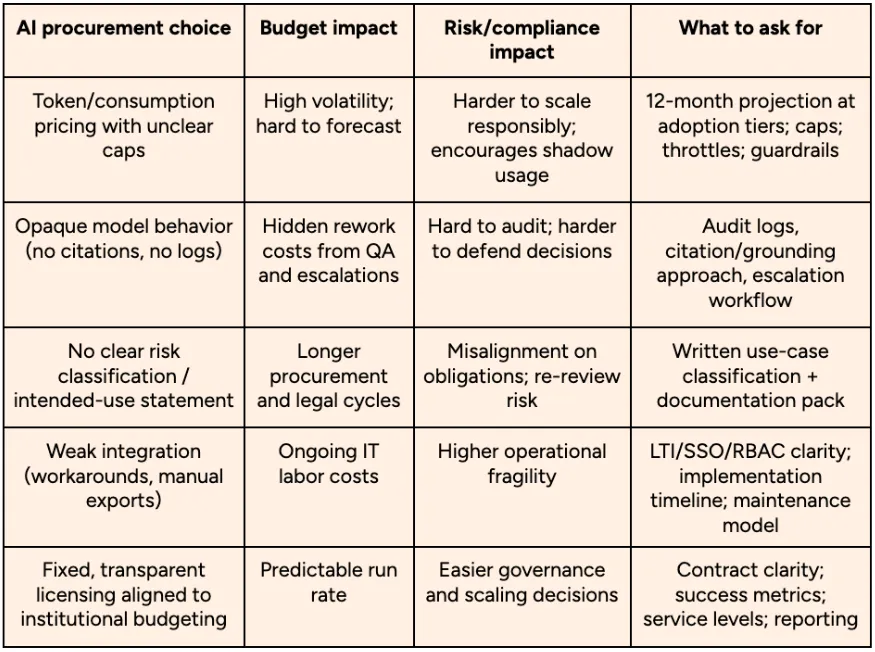

3.3 A practical cost–risk trade-off table (for budget owners)

3.4 A higher-ed friendly “AI Total Cost of Ownership” model

When you’re asked to justify an AI investment (or defend why you didn’t choose a tool), it helps to frame costs beyond licensing. A simple TCO model for higher ed includes:

- Licensing and renewal model: Fixed vs usage-based, plus add-ons and feature gates.

- Security + privacy review effort: Staff time (IT security, legal counsel, DPO), documentation back-and-forth.

- Implementation and integration: SSO/RBAC setup, LMS integration effort, knowledge ingestion, testing.

- Change management: Training, comms, internal support, governance cadence.

- Ongoing operations: Monitoring, audits, content updates, incident response, analytics reporting.

The AI Tool Evaluation Framework bakes several of these into the evaluation process explicitly, including: implementation planning (25/30/60/90 days), system update frequency, flagged response workflows, integration support (including LTI 1.3), and analytics/reporting examples.

The insight for budget owners is simple: a lower sticker price can be higher TCO if it increases review time, IT maintenance, and compliance uncertainty.

3.5 Quick actions that reduce cost without slowing adoption

If you want to keep momentum and protect the budget, take these steps:

- Standardize vendor intake with a single checklist (security, accessibility, privacy, governance, cost model).

- Require pricing clarity at scale, not just pilot pricing (include peak-term estimates).

- Classify use cases early (especially anything touching admissions, grading autonomy, or proctoring).

- Set baseline metrics before launch: adoption, deflection, time saved, and escalation rates, so your “ROI story” is built on evidence, not anecdotes.

Download the AI Readiness & Risk Assessment Checklist

Download the study

Download the whitepaper

Chapter 4: How institutions are evaluating risk-based AI vetting in higher education

By 2026, “AI risk assessment” in higher education won’t be a once-per-year policy exercise. It will look much more like what procurement teams already do for cybersecurity, accessibility, and enterprise systems: a repeatable intake process that moves quickly when evidence is clear, and slows down when risk is real.

The good news is that institutions don’t need to invent a complex governance machine to get there. In practice, the most effective approaches share a few traits:

- They standardize what evidence vendors must provide

- They use a common rubric so stakeholders score risks consistently

- They design pilots to test controls and operations, not just features

- They use the same workflow across AI use cases (support, tutoring, advising, feedback)

Tools like the AI Tool Evaluation Framework and AI Tool Evaluation Rubric are strong examples of how to make vendor discussions more transparent and evidence-based.

Below are three realistic “institution-in-motion” scenarios showing how risk-based vetting often plays out, and what good looks like.

4.1 Scenario 1: The CIO asks for “risk classification + evidence pack” before the pilot

A mid-sized university wants to run an AI pilot to reduce support load and improve student self-service. The vendor demo is compelling, and the student services team is ready to move. In the past, that enthusiasm might have triggered a quick pilot, followed by a long stall when legal and security enter late.

Instead, the CIO changes the process:

Before a pilot is approved, every AI vendor must submit an evidence pack.

The institution uses a simple two-step intake:

- Use-case classification (from Chapter 1): What is the tool doing? Is it making or materially influencing educational decisions?

- Evidence (from the evaluation framework): Can the vendor provide standard documentation now, not later?

The AI Tool Evaluation Framework explicitly recommends gathering:

- HECVAT (or equivalent security questionnaire response)

- Accessibility documentation, such as an ACR from a VPAT (or as much VPAT detail as possible)

- Additional privacy/security documentation (e.g., SOC2 Type II, FERPA-aligned materials)

- A clear explanation of ethics and governance practices (transparency, non-discrimination)

- A statement about institution environment separation (how institutional data is kept separate and not used in the larger model)

What changes when the CIO asks for this upfront?

- Procurement timelines become more predictable

- Legal and security reviews become shorter because the evidence is ready

- Pilots stop being “faith-based experiments” and become structured evaluations

How this typically shows up operationally:

The institution creates a one-page intake form and a shared folder where vendors must upload their materials before being scheduled for a formal review. Once the evidence is complete, the pilot can move quickly.

4.2 Scenario 2: Legal and procurement standardize evaluation with a shared rubric

In many institutions, legal teams get involved in AI reviews late and receive a pile of vendor marketing claims instead of operational proof.

A procurement lead solves this by making the process repeatable:

- Every AI tool is evaluated using the same scoring lens

- The rubric is shared across IT, legal, accessibility, and academic leadership

- Stakeholders rate risk consistently and document why

The AI Tool Evaluation Rubric is designed exactly for this purpose: it establishes explicit categories and risk thresholds across five areas:

- Accessibility & Inclusion

- Functionality & Technical Reliability

- Content Quality & Accuracy

- Ethical, Legal, and Financial Framework

- Pedagogical Impact & Fairness

This matters because it allows institutions to move beyond vague debates (“It seems safe” vs. “It seems risky”) and instead anchor decisions in concrete criteria.

For example, legal and compliance can focus on the rubric’s Ethical, Legal, and Financial Framework section, including:

- Data privacy & compliance (FERPA/GDPR)

- Intellectual property & data rights

- Cost of use and pricing sustainability

Meanwhile, IT and digital learning teams can evaluate:

- LMS integration & setup (including whether the tool requires extensions or external downloads)

- Technical stability and reproducibility

- Scalability & performance for large user groups

What changes when a university uses a shared rubric?

- Stakeholders stop repeating the same debates across departments

- Risk conversations become faster and more evidence-driven

- Procurement can defend decisions (“we approved this tool because it met X, Y, Z”) and reject others cleanly (“this tool failed A, B, C”)

How institutions operationalize this:

They attach the rubric to RFPs, then require vendors to show (not claim) how they meet each dimension during demo and pilot.

4.3 Scenario 3: An institution replaces a legacy chatbot after audit gaps appear

A university has a legacy “AI chatbot” that’s been in place for years. It started as a simple FAQ tool, but over time it expanded, answering questions that touch financial aid, academic rules, and support policies. Adoption is high, but risk review reveals problems:

- No clear audit trail

- No source citation or verifiable grounding

- Unclear data ownership terms

- Weak governance controls for prompts and content updates

This is exactly the kind of tool that can become a compliance and reputational risk, not because chatbots are inherently high-risk, but because lack of controls turns small problems into institutional exposure.

The rubric highlights these issues directly:

- Source citation & attribution: whether outputs are verifiable and properly cited (vs. unverifiable “black box” content)

- Data sources & coverage: whether the system uses reputable, up-to-date sources relevant to curriculum needs (vs. unknown or untrustworthy web data)

- Process transparency: whether the tool explains how outputs are generated (vs. entirely opaque mechanisms)

- Data rights: whether the institution retains ownership and whether student/institution data can be used for training or monetization

When these gaps surface, the institution makes a strategic decision: it stops treating the chatbot as a “nice-to-have” and starts treating it as institutional infrastructure that must meet enterprise standards.

What changes in the replacement process?

- The institution adds auditability and citation requirements

- It demands clear data rights language

- It requires stronger integration and identity controls

- It prioritizes tools that can be governed centrally and updated transparently

This is a common inflection point for institutions moving from “AI experimentation” to “AI governance maturity.”

4.4 What “good” risk-based vetting looks like in practice

Across these scenarios, the pattern is consistent:

Institutions that succeed don’t evaluate AI based on hype. They evaluate AI based on operational proof.

That means vetting becomes:

- Evidence-based (documents and controls come before pilots)

- Cross-functional (IT, legal, procurement, accessibility, academic leadership aligned)

- Repeatable (same steps for every tool)

- Scalable (the process still works when 12 departments want AI tools at once)

And perhaps most importantly: risk vetting becomes a way to speed adoption responsibly. It creates a “yes path”, so teams know what it takes to deploy AI safely.

Chapter 4 takeaway: make evaluation reusable, not reinvented

If your institution has to reinvent its evaluation approach every time a new AI tool appears, adoption will either stall, or go shadow. The most practical step is to adopt a shared checklist and scoring approach that can travel across use cases.

Download the study

Download the whitepaper

Chapter 5: How to classify and implement AI tools in higher education

The goal of AI risk assessment isn’t to slow adoption. It’s to make adoption repeatable, defensible, and easier to scale, so that AI becomes part of institutional infrastructure rather than a collection of disconnected pilots.

By the time you reach this chapter, you should have two practical advantages:

- You can classify AI tools based on what they do (not what vendors claim)

- You have a structured way to evaluate vendors using evidence, not intuition

Now the work becomes organizational: turning that clarity into a simple operating model your institution can sustain.

Below are four next steps that keep the tone calm and collaborative - because long-term AI governance works best when it’s framed as shared enablement.

5.1 Centralize policy and tool classification

Most institutions don’t need dozens of AI policies. They need one clearly owned, centrally discoverable place where anyone can answer:

- What AI tools are approved?

- What uses are permitted (and not permitted)?

- What is our risk posture for different use cases?

- Who owns updates, exceptions, and review decisions?

A simple but effective approach is to create a single AI governance hub that includes:

- A short institutional position statement and principles (what “responsible AI” means here)

- A list of approved tools and approved use cases

- A clear evaluation pathway (“If your department wants an AI tool, here’s how”)

- Risk classifications or risk notes for common AI categories (tutoring, feedback, support, analytics)

For inspiration, check out some real-life examples:

- Purdue University's Tool Evaluation Guide: Provides a detailed breakdown of criteria for departments to use when vetting tools, covering privacy, ethical considerations, and integration capabilities.

- The National Forum (Ireland) Procurement Guide: Offers a structured template for vendor procurement, involving Data Protection Officers (DPO), IT security, and accessibility leads.

As always, the key is consistency. When policy and tool classification are scattered across committees, SharePoint folders, or email threads, adoption becomes uneven, and shadow AI becomes more likely.

5.2 Share readiness frameworks internally, and champion a common language

The fastest way to reduce friction between IT, legal, procurement, accessibility, and academic leadership is to give everyone the same evaluation vocabulary - that’s what the AI Readiness & Risk Assessment Checklist is for.

Instead of each team asking different questions at different stages, the checklist becomes:

- The intake form for new AI requests

- The structure for vendor calls and evidence collection

- The shared record of why a tool was approved, restricted, or rejected

Make the checklist available in a shared location and assign clear ownership for:

- Who receives requests

- Who completes which sections (IT security vs legal vs accessibility)

- How decisions are documented

This also makes evaluation more equitable. Departments learn what “good” looks like, and approvals stop depending on who has the loudest champion.

5.3 Vet current vendors and clean up shadow AI use

One of the most useful moves institutions can make is also one of the most sensitive: acknowledging that AI is already being used informally.

If the message becomes “we’re cracking down,” adoption goes underground. Instead, approach it as a practical improvement initiative:

- We want staff and faculty to use tools that are safe, reliable, and compliant.

- We want to reduce duplication and tool sprawl.

- We want to make it easier to get to “yes” when the evidence is there.

Start by identifying three categories:

- Approved and well-governed: Tools with clear contracts, documentation, and controls.

- In use but not evaluated: Tools being used departmentally (or personally) that may touch institutional data or student content.

- High-risk or inappropriate for institutional use: Tools that lack auditability, have unclear data rights, or create budget volatility.

The outcome you want is not punitive. It’s a cleaner, safer baseline:

- Fewer tools doing overlapping work

- Clearer ownership

- Fewer uncontrolled data flows

- More consistent student experience

Shadow AI use typically grows when the official process is unclear or too slow, so the solution is to provide a clearer route and better options, not just enforcement.

5.4 Establish an annual AI review process

AI systems evolve faster than standard edtech tools. Capabilities that weren’t present at contract signing can appear later through updates: new features, new models, or expanded data access. That’s why institutions should treat AI classification as living documentation, not a one-time decision.

An annual review cycle should include:

- Re-confirming each approved tool’s intended use (what it is actually being used for)

- Re-checking sub-processors, data routing, and retention policies

- Reviewing audit logs and usage patterns (including where the tool is being used beyond initial scope)

- Updating risk classification if functionality changes (e.g., advisory feedback → autonomous grading)

- Ensuring accessibility documentation remains current

The goal is to build institutional muscle: a routine that prevents surprises, keeps procurement decisions defensible, and ensures AI adoption remains aligned with policy and learner trust.

Get the resources

If you want to operationalize the approach in this guide, these two resources are designed to be shared directly with committees, procurement, and governance groups:

Download: LearnWise Product Classification Documentation (PDF) Use as a reference example for how classification is documented and how feature configuration affects risk posture.

Download: AI Readiness & Risk Assessment Checklist Use in vendor calls, RFPs, pilot gating, and internal decision-making.

Conclusion

AI risk assessment in higher education doesn’t have to be intimidating, or a blocker to progress. When institutions classify AI tools by intended use, evaluate vendors using consistent evidence, and align stakeholders around a shared checklist, AI adoption becomes more manageable, more defensible, and easier to scale.

The most important shift is structural: moving from one-off pilots and fragmented approvals toward a repeatable approach that supports innovation while protecting student trust, institutional data, and budget predictability. With a clear classification model, a standardized evaluation process, and an annual review cadence, teams can make confident decisions even as regulations and tools evolve.

.png)

.webp)

.webp)

%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp)